Engineering With Purpose: How Students Are Driving Global Change

Across the globe, student chapters of Engineers Without Borders USA are tackling some of the world’s most pressing infrastructure challenges: clean water, sanitation, and climate resilience. These student-led teams bring technical skills into real-world settings, designing solutions that are locally informed, environmentally responsive, and built to last.

At UC Davis, students redesigned household latrines in Bolivia to better fit the needs of farming families. In Rwanda, Clemson students co-developed a spring box and began designing school water infrastructure to support over 3,000 students. And in Malawi, the University of Delaware has spent years refining how to locate underground water sources, navigating the uncertainty of resistivity testing to drill wells that serve entire villages.

Together, these stories show the power of student engineering teams when they approach development work with humility, curiosity, and a commitment to partnership. Their stories aren’t just about engineering practice; but resilience, patience, and impact.

UC Davis in Bolivia: Reinventing Sanitation to Protect Livelihoods

In the rural Andean community of Parque Colani, Bolivia, many families lacked access to safe, sanitary latrines, which posed serious health risks and threatened water sources shared by the entire village. In response, the Engineers Without Borders UC Davis chapter partnered with local leaders to co-develop household sanitation solutions that were practical, affordable, and respectful of how people live and work.

The team’s initial latrine design, developed during pre-trip planning, followed a common format: a pit dug adjacent to the superstructure, connected via piping. But once the students arrived in 2023 for implementation, they encountered a challenge they hadn’t anticipated. In a farming community like Parque Colani, every square meter of land matters, and the space required for the offset pits was cut into valuable agricultural plots. Families were hesitant to give up growing space, even for sanitation.

Rather than pushing forward with the original design, the team took a step back. They consulted with community members, their local contractor Pancho, and UC Davis faculty advisors to revisit the plan. The result was a more compact, stacked design which placed the superstructure directly on top of the blackwater pits. This approach saved space, made maintenance simpler, and better aligned with the community’s needs. But it also created new engineering challenges: how to safely support the weight of a concrete structure over a void?

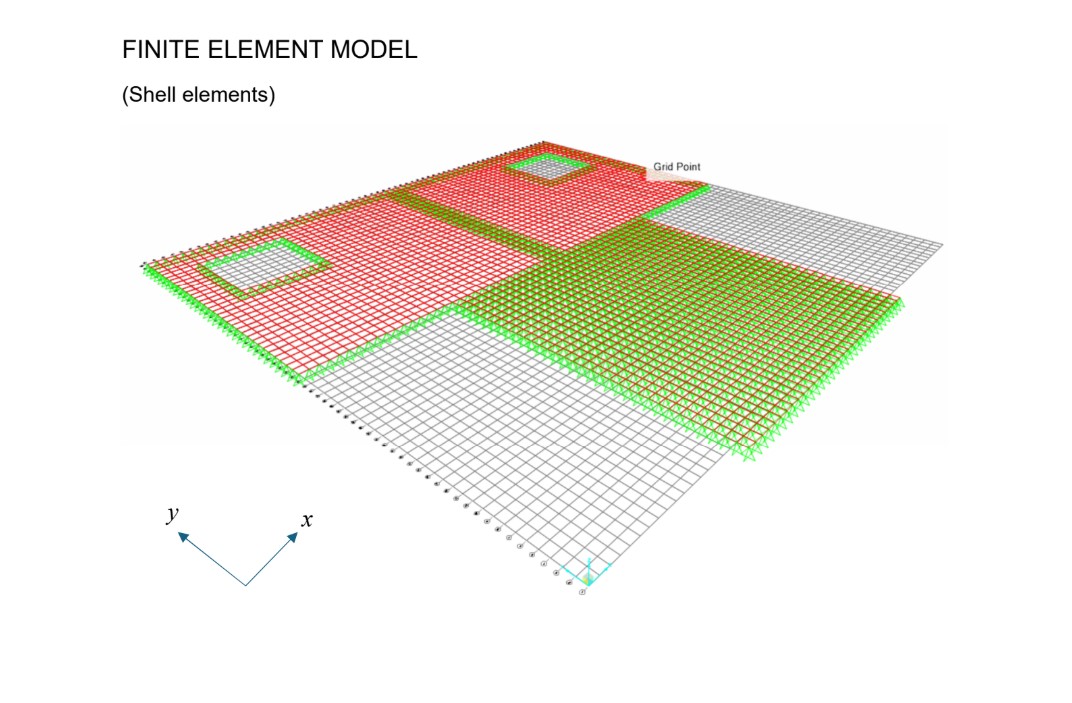

To solve this, the students dove into structural design. Working with UC Davis professor Sashi Kunnath, they developed a reinforced concrete slab with custom rebar placement that could safely bridge the dual-pit system. They balanced strength, material availability, and constructability ensuring that the new design could be built with local tools and knowledge, and maintained long after the team’s departure. The solution wasn’t just technically sound; it was community-ready.

This work represents the core of EWB-USA’s approach: engineering that adapts to context, co-creates with communities, and makes space for learning and iteration. For the families of Parque Colani, these new latrines are more than a health intervention; they're a reflection of partnership, respect, and thoughtful design that supports both public health and agricultural livelihoods.

Clemson University in Rwanda: Building Clean Water Access from the Ground Up

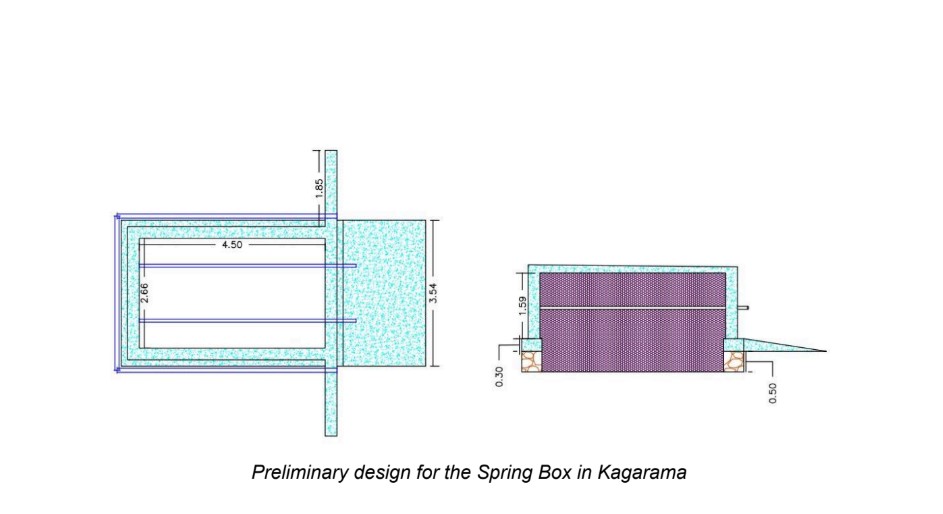

In the rural outskirts of Kigali, the community of Kagarama has long relied on a contaminated seepage spring as its only water source that exposes residents to bacterial contamination and chronic health risks. Since 2023, the Clemson University chapter of Engineers Without Borders has been working in partnership with local NGO Integrated Development in Action (IDA) to design a sustainable water access solution. Their goal is a protected spring box that provides reliable, clean water to all 1,500 residents.

During a Spring 2024 assessment trip, Clemson students and their professional mentors conducted extensive fieldwork to evaluate the site. They ran water quality tests confirming turbidity and bacterial contamination, mapped site topography, and performed flow analysis finding the spring’s output was a promising 4.6 liters per second. Perhaps most significantly, they met with community members and local government representatives, who expressed enthusiastic support for the project and a shared commitment to making it work.

Back in South Carolina, the team got to work on the technical design. With guidance from professional mentors and structural experts, they developed a seepage collection-style spring box tailored to the site's conditions. The structure is designed to withstand internal water pressure, backfill weight, and erosion risk while offering a projected lifespan of over 50 years with minimal maintenance. More than a water source, the spring box represents long-term security for a community that’s never had safe water access.

But Clemson’s impact in Rwanda doesn’t stop there. During their assessment trip, the team also identified a new need at G.S. Musave, a nearby K–12 school with over 3,500 students. The school receives municipal water only one day per week, forcing students and staff to rely on limited rainwater storage and untreated sources. The chapter is now preparing to assess the school’s water infrastructure during their upcoming trip, with the goal of integrating additional tanks and a gravity-fed filtration system into the existing setup.

Meanwhile, Clemson’s newly formed Water Equipment Testing Team has been working behind the scenes to inventory materials, train new members, and develop low-cost filtration systems for future projects. From the field to the classroom, the chapter is building not only infrastructure, but a lasting culture of collaboration, innovation, and student leadership in global development.

University of Delaware in Malawi: The Art and Uncertainty of Finding Water

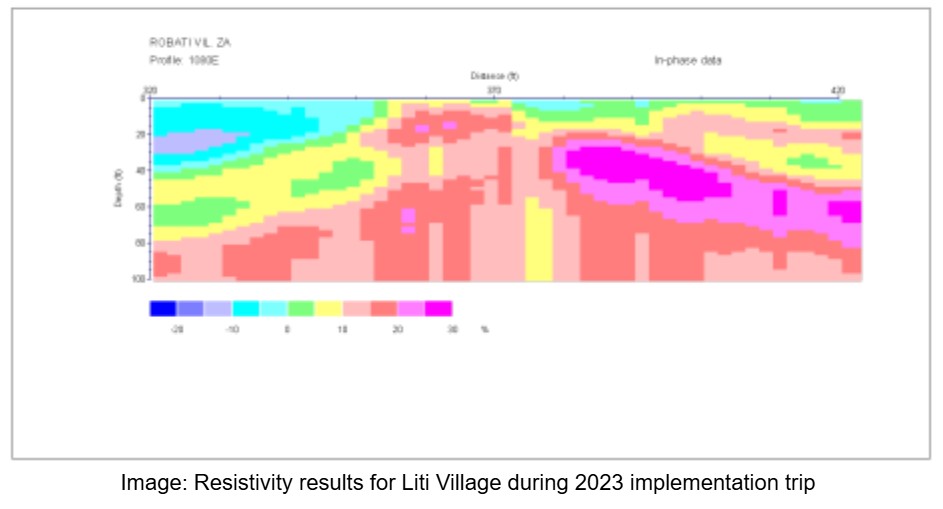

For over a decade, the Engineers Without Borders USA chapter at the University of Delaware has partnered with communities in Malawi’s Sakata region to improve access to potable water. Over the course of six well installations across four villages, one challenge that has consistently defined their work is how to locate groundwater in a region where drilling is expensive, uncertain, and often unsuccessful. The tool at the heart of this process is resistivity testing, a method that’s part science and yet part art.

Resistivity testing works by sending electrical currents through the ground to detect changes in resistance. Because water has low resistivity and the surrounding rock has much higher values, this technique helps teams infer where underground aquifers might lie. It’s not a precise science, but rather a process of interpreting subtle electrical shifts in the landscape to make the best possible guess.

That lesson became painfully real during a recent implementation trip. After interpreting resistivity data and selecting a drilling location, the team’s first well came up dry. The setback was disheartening, but also a catalyst for learning. The team brought in a more experienced local contractor to conduct a second round of resistivity testing, asked tough questions about methodology, and discovered that the process varies dramatically from one technician to another. There are no universal benchmarks or guarantees: only experience, interpretation, and trust.

With renewed insight and support from mentors, the students selected a new drilling site. This time, they hit water, successfully completing two wells during the trip. But the challenge didn’t end there. Their next goal takes them closer to a nearby saltwater lake, where the presence of brackish water could interfere with resistivity readings and water quality alike. Not only must the team find water, they must find water that’s safe to drink.

For this chapter, the work in Malawi isn’t just about hitting a target underground. It’s about navigating uncertainty, building cross-cultural trust, and pushing their own understanding of what it means to be a problem-solver. The result is not just wells, but a generation of engineers learning to thrive in the unknown.

Learning by Doing, Leading Through Partnership

What unites these student projects isn’t just the technical challenge. It’s the way each team has responded: with adaptability, deep listening, and a willingness to grow. Whether it’s rethinking a latrine design to preserve farmland, co-developing long-term water access in a rural school district, or grappling with the uncertainty of well drilling in Malawi, these students are doing more than executing designs. They’re building trust, questioning assumptions, and learning to engineer with, not just for, communities.

This is the heart of the EWB-USA experience. It prepares students not only to become better engineers, but to become thoughtful collaborators and future leaders, people who know that good engineering is about more than getting the numbers right. It’s about asking the right questions, respecting context, and creating solutions that last.